by Charles Bowden

The pile of Aperture issues rests on the clean table as cool north light seeps into the old brownstones. I tell myself to think of the half century of issues, sequencings, arguments, and folios as nothing more than flash cards flaming past the eye. I let this blur burn my face and then, I start to understand a little bit.

I seem to die a little bit every time I look at photographs. The woman in the tight dress now can’t wear it, that war is over, we don’t sport hats these days, I don’t play baseball anymore, and wasn’t he famous once? The photos are always then, and I’m always now.

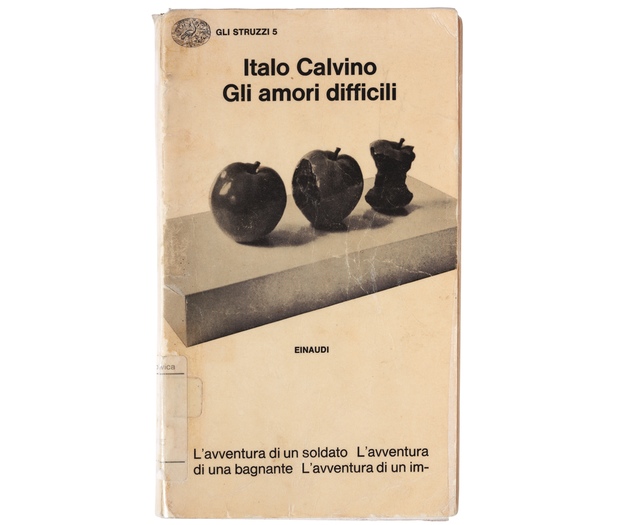

![]()

Paul Strand, The White Fence, Port Kent, New York, 1916

There are two other things: I always believe photographs, no matter what I might claim. And I am never intimidated by them. A painting, a poem can face me down as some kind of test. But snapshots have made the output of cameras safe for me. I suspect this feeling of comfort with photographs is common.

As a boy, I found an old photograph in my aunt’s attic and when I looked at it I inhaled a world: I smelled the zinnias, snap-dragons with coarse leaves, blue hydrangeas drooping on the lawn, insects thrumming, the early morning coolness. The dirt smells rich and rank. Morning still hangs in the shadows, and the world is cool like a stone milk-house. All those white chickens by those red wheelbarrows in the yard promising a hard, sure reality where everything is deliberate and nothing is a mystery. Paul Strand points his camera at a white picket fence in Port Kent, New York in 1915 and nails this same chord of visual music that I stumble on in my aunt’s attic, this insistence on the physical reality of the moment.

I can tell. Always, when I look at photographs, I know I can tell what is going on. There is something about photographs that makes us look.

Aperture begins by insisting on an actual world. Lisette Model orders a drink in the blue air of Sammy’s bar in Manhattan, Dorothea Lange captures a signpost at the crossroads, that first cover. Beaumont and Nancy Newhall help prop up this early Aperture, and Nancy lances the tissue of the early issues with essays that cut through artspeak like a scalpel. Barbara Morgan flings dance on the page. Minor White is the soul of the magazine for more than a decade.

The magazine is a tiny thing, and at first it offers a kind of editorial clearing of the throat with fragments of photojournalism—Lange’s embattled America, Lewis Hine with those immigrants shuffling up a staircase at Ellis Island, Ansel Adams’s West, Frida Kahlo, and there’s Marlene Dietrich looking just so in those portraits, early shots of the Pyramids, the waters rising to slaughter a farm valley in California. And then it shifts and amid the little essays in the fifties, the essays that said here is what a professional photographer must do and be, here is how to run that camera, amid these didactic teach-ins, White seeks a kind of deep imagery that signals a connection with an imagined eternal world. One issue has an offhand shot by Barbara Morgan of a girl sitting on a rock playing a recorder. The image is as ancient as a shepherd on a hillside in the Greece of Homer and as recent as the date in the caption: 1945.

I am sitting in Oregon almost a half-century after finding that old snapshot in the attic and I’m talking with my sister on the deck of her house against the mountain. She is taking a hundred pills a day because of the illness and all of her hair has fallen out. I guzzle a glass of wine she is forbidden. I mention the image I found as a child and she is suddenly alert. She goes into the kitchen and fetches an old snapshot taken on the farm: she is maybe seven, in a dress, blond hair, eyes squinting in the sun, I am four, hair cropped like a convict in the uniform style favored after the end of that war.

I tell her of the eerie quality of that old photo I once found, the one that has triggered our conversation. I tell her it had no aesthetic merit, and no explanation but that when I stumbled upon it as a child, I instantly knew what it was and could move beyond its borders and wander the world it came from. There was no date on it, nor handwriting explaining any circumstance. Almost fifty years ago, I climbed up into the attic of my aunt’s farmhouse in Minnesota. I was eight or nine or ten; it was late morning. Dust floated in the air and lay deep on every object, a menagerie of broken chairs, old chests, trunks suitcases, cheap novels. I remember I was looking for hard goods, maybe an old pistol or decommissioned shotgun.

I found the photograph.

A man and a woman sit on the grass. They are very close and stare at the camera. The man wears slacks, suspenders, a white shirt, and glasses with round frames. The woman has a print dress, her hair up in something like a bun. The man is my father, the woman I do not know. But instantly, in the dust and light and shadow of the attic, I know this is my father’s woman. I have never heard of her. Or of much else in his life. Nor will I ever hear much, he was not that kind of man. But at that age in that attic, I instantly knew what was going on in that photo, right down to the flowers blooming outside the frame and time of year and the sounds and smells that have just been in the air, and I knew the woman was no stranger to my father.

I think much of the history and frustration of photography is in that cheap, off-handed image. Photographs convince us.

Minor White explains that there are Seven Levels of Light. He gives out the task: “Illuminate the mind and cast shadows on the psyche.” Minor White cannot be escaped. He is the tortured man who survived World War II better than he did the iron peace of the Cold War. He infused the first decade or more of Aperture with both his faith and his inner turmoil.

“It was a one-man show,” he later noted, “an outlet for my own photographs . . . My own photographs, but other people did them.”

In the early sixties, Minor White decides to end Aperture. He listens to some internal clock in these matters. The thing he has nurtured has a circulation of about 450. And Aperture, an idea fomented by a handful of people in the early fifties and nursed into life and form by White, goes into a free fall, like a drying print that slips loose of the clothespins in a darkroom, flutters off the line and slowly floats to the floor. Michael Hoffman, a student and product of White in Rochester, bounced around the West for a spell, rode the rodeo, and most importantly, Hoffman had the kind of energy and focus required to make something work. It is as if a slumbering volcano suddenly erupted. Aperture becomes a foundation, prints, hundreds of books, and a menu for those curious about what to see and how to see and why to see. Paul Strand, at the end of his career, becomes part of the springboard for this new Aperture when he leaves his archive to the foundation. Aperture finds its way to the future by walking on the photographic bones of the past: Strand’s stark, loving studies of other places, White’s distillation of a lifetime of sequencing in his final testament of books.

I find this Aperture in a small bookstore in Arizona, when I pick up a small volume on Roger Fenton, part of some “Masters of Photography” series, the cover claims, and begin to teach myself how to see by looking at the world through the eyes of people who saw what I missed. A woman shrouded in the yards of requisite Victorian clothing walks the path at Windsor and this world looks so spacious and empty and lonely that I can hear the rustle of her long skirt against the gravel walk. I’d never heard of Aperture and pretty much thought photography was about picnics, weddings, newspapers, and magazines. Michael Hoffman’s Aperture opened up a new world to me. As it happens, the very world I’d always lived in but could not see.

As I write this, Michael Hoffman has just died at age fifty-nine in a New York hospital. I never met him or spoke with him and so I am in a position that most readers of this magazine share: I knew him by his works. He’s the guy who introduced me to Diane Arbus, Edward Weston, W. Eugene Smith, Dorothea Lange, and a long list of other wizards with cameras. He dragged the poor into my house in books by Sebastião Salgado and Eugene Richards, he made me look at the Chinese hand in Tibet, and the mafia slaughter of Sicily. The Aperture I stumbled upon in a bookstore in Arizona was the face and voice of the man I never met. I used to sit around at night browsing Aperture’s catalog like it was a candy store with open stock. Whatever Aperture now becomes is up to us. But what it is now is what Michael Hoffman created. A lens that could penetrate even my desert hut in Arizona.

You just can’t get to the life of photography without facing all the death in photography. The image is always about the past and this knell of the past is what keeps forcing us to listen to photographs, including those that only trace the evolution of our own faces. Fossils are created in the darkroom.

This is how it goes: I am driving across Nevada at eighty miles an hour, the miscellanies of Minor White flashing across my mind, when I succumb once again to the power of the dead.

I know the sea is down and they are writhing as the sun torches their sensitive skin. There are forty of them marooned in a small mud flat as the waters pull away and decline and this retreat is fatal for them, this retreat of the sea that will leave them dry-docked for two hundred million years. The jaws are powerful for ripping flesh, the body long and firm, running to sixty feet, the fins propel them at twenty-five miles an hour. They fit uneasily into categories, half-fish, half-reptile. They are on the path towards being fossils and the mud will catch every detail of their bodies, the minerals will slowly leach into their bones, gold and quartz filling them cell by cell, making them rock, and the imprint will be so exact that my kind will glance at this negative imprint of their lives and know that they gave live birth, know this fact two hundred million years after the collision of their sexual congress has ended.

In 1977 they are declared the official state fossil of Nevada. They now exist seven hundred thousand feet above sea level in the Shoshone Mountains of central Nevada. They are called Ichthyosaurus Shonisaurus popularis and scholars explain their doom by tectonic-plate movement and uplift and a scale of time that terrifies most people. They look up from stone and I blink and think, Christ, this half-fish-half-reptile has just made one of the first negatives.

I always seem to wind up driving along a lonely highway, storming north at eighty miles an hour toward that visit with my sister in Oregon and in my head I have this heavily plotted conversation I’m going to have with her about the image I glimpsed fifty years ago in my aunt’s attic. I sip stale coffee as the Shoshone Mountains huddle to the north, the sky is overcast, the desert rich in soil color under filtered light. There are few signs of people save the occasional whorehouse that pops up as a cluster of trailers. Fossils everywhere, including in that next frame to be shot.

I pull off at Goldfield, Nevada, a mining town that around 1906 was home to thirty thousand people. The major saloon then required eighty men to tend what was called “the world’s longest bar.” By 1910, this was ending; by 1920, the whole county of Esmeralda held only 2,148 and today it harbors a little over a thousand. Goldfield itself struggles on as a friendly ruin.

I was here once before, in 1959, at age fourteen on my way to Seattle with my father. I was driving so that he could sprawl on the bunk he’d build in a converted bread van and drink without worry. We pulled off in Goldfield because he knew Wyatt Earp had once frequented the area during the boom when he had a liquor and tobacco store. The old man was a fount of such details. We walked past the ancient hotel, a sturdy building, and when I looked in the tables were still set in the dining room, the silver right by the old china.

The old man was in his early sixties, beer-bellied, the stubble of a three-day beard on his face, a baseball cap on his gray head, tri-focals taking in the scene and he looked nothing like the yearning figure in that photo in my aunt’s attic who seemed attached to the woman beside him on the grass. He did not know that I knew of that image or of that woman. I would never bring it up. My father did not answer questions or care what anyone living or dead thought of him. Six years later, when my sister married, he told her that he had been married before and that the marriage did not work and he got a divorce. He told her this, and nothing more, in an effort to comfort her in his clumsy way, so that she would not worry should her marriage fail. And he revealed this just before the wedding. He never told my brother, who is nine years my senior. And of course, no one ever asked him anything about it.

So in 1959, we walked the empty streets of the dead town and came upon a saloon, Silver Dollar Kirby’s. The old man went in and the bar was a plank on two sawhorses, the stock one or two bottles and some shot glasses. He ordered a double and threw it down.

He asked the bearded ancient—Silver Dollar Kirby—“How is it going?”

The graybeard answered, “I get by,” and then paused in deep thought and added, “Well, I’m setting a little aside, too.”

Now I am back, a little over forty years later. The old man is dead, Silver Dollar Kirby long gone. And when I ask at the tiny Goldfield chamber of commerce for the local population figure, I’m told, “They say it is two hundred.”

The town, whatever its numbers, still hosts five saloons.

I can see my father walking down the empty street to a bar, I can see the photograph in the attic, I can hear the sounds of the dying Ichthyosaurus. If you want to talk about where photographs come from and where they go and what they are about you will, in the end, come to the Goldfield, Nevada of your life. And there you will find a sequencing that escapes the shackles of prose. You will look at the fossil of the dying fish/reptile and right before your eyes will appear the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky who is busy killing himself as the sullen weight of Stalin’s Soviet Union fell on his shoulders in the 1930s. There, quite near the body, he has left a final note: “The love boat has crashed against the everyday. . . .”

The emotional response to a photograph is very close to feeling the breath of a prehistoric beast on your neck.

Photography has moved past the debate about whether or not it is an art. Photography has ceased to be a debate about what is and what is not a photograph.

But photographs cannot escape their fate as fossils, as moments of life frozen on paper. And viewers cannot escape their appetite for the content of photographs, an appetite so severe that it often overwhelms standards of aesthetics. O. Winston Link’s ancient steam locomotives look beautiful. But bad photographs of steam locomotives are also oddly compelling because the things within such prints have disappeared. Photography seems to hate borders and consumes just about everything with relish.

In the seventies, and more especially in the eighties and nineties, Aperture gave up on the tutorial and started ranging widely, a beast feeding off the past, then shredding that past with folios of images that had been written on, cut up, had things pasted on them, were held down to the floor while all these new computers had their way with them. Aperture became a place with all kinds of things claiming to be photographs and a lot of people, myself included, kind of get miffed at these antics from time to time. But mainly I think I got upset with such experiments because photographs have content, and in my hidebound way, I didn’t want this content tinkered with by the comments of the photographer—a strange position since the photographer has already scribbled a comment by picking up the camera and framing the shot.

Basically, photographs, cause debate because they incite belief. People want beauty and then, when they get something they’ve heard rumored on the front pages of newspapers, now made solid by images, they want to turn away from these visual reports. And what really upsets most of us, and this is the curse of photographs, is that it is so hard to turn away. Once I see a powerful photograph I cannot seem to erase it, try as I may. But after I’ve enjoyed my tantrum what I like is this: photography can now be damn near anything; the coal miner black as he comes out of the shaft, the spray of pigment in a landscape, a swirling form made with, say, a long exposure and blasts of colored lights. Photographs can be that beauty thing. And they can be that other thing, the thing that sent Kurtz reeling out of the Congo and into the imagination forever: the horror. There is still that tug of Ansel Adams and his shots of some Eden, but my mind cannot help placing them next to Richard Misrach and his nuclear cows dead on the Yucca Flats of our new West.

I have been staring at the work of Tina Modotti as I sit in the wet sun of Oregon. I have looked at the early shots of Talbot and Daguerre and Fenton and others. I believe in Atget’s streets, all 8,500 shots of his imaginary Paris freed from modern machines. I stare into the hard sharp surfaces of f.64, the early flowerings of Aperture as Minor White plunges like an Ichthyosaurus into deeper waters where he senses something eternal hides beneath the waves of life. I have taken to eating pears from the Oregon orchards.

My sister says she heard the woman in the photograph was crazy. Neither of us can remember her name now.

I say that she was a heroin addict, that I know this for a fact but I cannot remember if my aunt said this, or the old man once told me. I have other scraps: once, after our father remarried, our mother recalls the woman’s brother came by the farm. The woman was dead then, of course. And our father and the visitor went out in the farmyard and talked and then the brother left. That is all our mother knows. She could not hear what they said and she did not ask. She tells me the woman’s name was Lillian and I roll it around on my tongue like a jewel.

My sister has a cup full of pills before her on the table and as we talk she steadily takes them, one by one.

“There was something about breaking dishes,” she recalls, “how she would throw the dishes against the wall, or they would both throw them. I think our aunt told me this. I can’t remember. She was also put in an institution once or twice, I remember something about an institution.”

My sister looks at me and says with a smile, “I can deal with anything but the future. Now I have trouble with the future.”

I have seen a photograph of the fossil of the Ichthyosaurus—it looks exactly like a negative: the beast is flattened and yet every detail is there, the teeth, the long porpoiselike mouth, the big body and flippers and fins, the immediate sense that it is a voyager from another time but yet an actual thing, not imaginary, as real as Lillian breaking dishes or loading that syringe or sitting with my father on the grass that promises an endless summer under the sheltering trees with red zinnias nearby.

My mother once told me my father would not remarry until his first wife was dead. I don’t know, I just know about the red zinnias and the snapdragons that are not even physically present in the old photograph. And I know the trapped beasts on Shoshone Mountain writhed as the sun ate their dying skin.

A few days ago, a friend stopped by and I was lost in photographs, staring at vanished worlds and worlds that keep returning. He mentioned a time long ago when we’d both run amuck and stuffed ourselves with drugs and how this experience, now long past, had opened up his mind.

I said this had not happened to me, that I must be some kind of mutant, that when I was young and swam for a season in a sea of chemicals the experience simply confirmed my day-to-day world. I seem to have been born stoned, I mused. I always heard colors, walked through photographs and went around corners and up blind alleys; every window I saw in an image I could enter, like a burglar, and then prowl the inner domains. The nudes always had scent for me, the tumult of the photojournalist was home, the serene rocks and frost on glass panes of Minor White were surfaces I knew before I was born. I had lived a life of déjà vu, and drugs, like photography, seem to enforce this sensation. I have no theory for this, no beliefs, no secret bottle of Carl Jung I keep on the side and toss down under a full moon. Some things simply are.

Homo sapiens is a haunted species. I cannot imagine Ichthyosaurus, even when dying on what would become the Shoshone Mountains, wailing over its fate. But people do and they reach for the camera to capture this sense of their lives passing—passing even though they seem to have just arrived. People are love boats filming their collisions. When their time as lovers has ended, and Tina Modotti slept alone in the house she had shared with Edward Weston in Mexico City, she wrote him, “. . . I accept the tragic conflict between life which continually changes and form which fixes it immutable.”

Minor White once wrote a strange phrase, “Circumambulation of the Light.” And then he advised, “It’s but another step into the dark room.” Yes, I must go now to the dark room. I must go to the old snapshot in the attic and admit this image is not very good, not well exposed, indifferently framed and lacking attention to contrast. The Ichthyosaurus isn’t really art, isn’t really a photograph, isn’t really a negative outside of my clever claims, but like the snapshot it does capture my attention. I look and look hard. Lewis Hine’s immigrants shuffle up that stairway, and I feel some chord struck within me. Dietrich stares up in her pantsuit and top hat and my God I can’t take my eyes away. It’s her, I know it. Charis is naked and Weston captures all those curves, a storm is lifting off the Yosemite Valley and Adams waits for the right instant, Stieglitz hunts the clouds, Lange keeps insisting on stories within every single shot she makes, White is mesmerized by the steam forming frost on the winter windowpane in Rochester, then come all those wars and demonstrations and bluesy nights and someone on a mattress in the East Village is shooting up, Mary Ellen Mark is flinging a teen prostitute into my face and strange visual reports arrive from mysterious continents of the earth. There is an endless roll call of powerful image makers, Sebastião Salgado, Richard Misrach, Sally Mann, Eugene Richards, William Eggleston, Graciela Iturbide, Don McCullin, Cindy Sherman, Robert Frank, Imogen Cunningham, Eugene Smith—who the hell am I forgetting?—and so many themes to explore and rend apart and return to and try to understand again. And I believe it all.

I may like paintings but I seldom believe them—that’s why hotels hang paintings in the rooms and never dare hang a photograph over the bed. I always believe photographs, no matter how fake or inept they are. My father sitting on the grass, the woman is by his side, and they have to be lovers—don’t try to say different—and just outside the frame those red zinnias thrive, the cattle low, and morning coolness hides in the shadows.

I can tell.

And so can you.

______

“The Other Life of Photographs” was originally published in Aperture magazine, issue #167, Summer 2002.

The post The Other Life of Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.