This essay appears in Aperture #209, the winter 2012 issue of the magazine.

By Tim Davis

Photography used to be a blue-collar job. You were on your feet all day, out in the elements, hands in chemical baths. Now it’s white-collar; in front of a monitor. Still I went ahead and bought a digital camera, thinking it’d make my world time more fluid. I could walk faster than I did with the view camera I’d been shouldering all my life, and it would balance out the screen time (which I call “watching TV”). This was 2008, and the world was turning loud and ugly. I would stroll around the small cities within my reach, being the Bear Who Went Over the Mountain. Remember why he did that? To see what he could see.

I didn’t make too many good pictures with that digital camera. It was almost as if, with every frame costing me nothing, I couldn’t make a picture matter. But it was okay for collecting. A digital camera makes a good Sherpa; it can carry your necessaries. I listened to the news on the way to these small cities: the Republicans were blaming the poor for the financial meltdown. Seems they had gone and bought a bunch of houses they couldn’t afford. Neil Cavuto on Fox News came out and said it: “Loaning to minorities and risky folks is a disaster.”

But on the achy streets of Newburgh and Scranton and Pittsfield and Troy, it became obvious that very few of these “risky folks” owned their own homes. Mailboxes were festooned with names and coated and recoated with paint as families moved on. People rented, and their mailboxes told tales of just how hard it can be to get housed. These streets were very far from Ronald Reagan’s imaginary “Cadillac-driving welfare queens.” There were gas stations where the corner store ought to be, bathing porches in troubling alien light. Instead of McMansions bought with WIC checks, a lot of this country lives in an unzoned miasma of the almost-commercial. America loves its flux, and where we live is rarely solid, rarely stable. And it’s always been that way.

De Tocqueville noticed how functional America’s landscape was: “If they repudiate all ornament from their architecture, and set no store on any but practical and homely advantages, it is not because they live under democratic institutions, but because they are a commercial nation.” Carleton E. Watkins was the first great poet of the American practical landscape. No one doubts why Watkins was photographing. A childhood friend of Collis P. Huntington—one of the robber barons Ambrose Bierce would refer to as “railrogues”—Watkins worked for logging and mine companies making majestic mammoth-plate pictures of their claims and processing plants. In among the factories and log piles, you can sometimes see where people lived. In Hacienda, View East, 1863, the sprouting hamlet of New Almaden, California, trails off in the distance like tailings of the quicksilver mine enveloping the foreground. Housing in Watkins is almost always an afterthought to commerce. Tiny clapboard houses cling to the San Jose road like remoras on the mouth of a shark, hoping for scraps. The landscape is so barren, the nonpanchromatic film emulsion blasting the blue sky white, that it is difficult to imagine anyone living in this place except to work. It had only been fourteen years since Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimac Rivers, where he noticed: “Men are as busy as the brooks or bees, and postpone everything to their business; as carpenters discuss politics between the strokes of the hammer while they are shingling a roof.”

It is difficult to look at this image without imagining all this activity burning itself out. Today the mine is the perfect American hybrid: a Superfund site and a museum. The village’s population hasn’t changed since 1863. Its most famous resident, Pat Tillman, died on a hillside in Afghanistan that would not look odd superimposed into Watkins’s photograph.

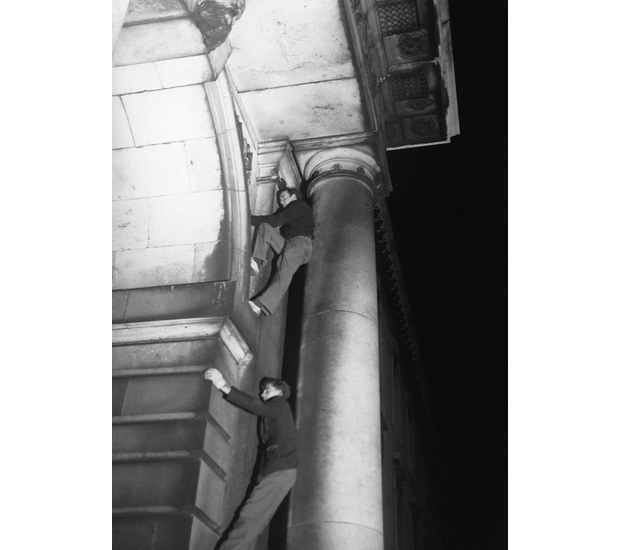

In America the landscape changes. And so house and home, the very seats of human stability, are always subject to alteration. Zoning is a relatively new concept here. There was none at all until the rise of the Progressive movement in the teens. So, in 1936, when Walker Evans and Peter Sekaer rolled through the South following an itinerary set by Farm Security Administration director Roy Stryker, they found natural clashes between the domestic and the commercial. Evans’s signature image, of two Atlanta frame houses bounded by a wall of billboards, perfectly describes the commercially contingent state of U.S. housing.

The long lens on Evans’s 8-by-10 view camera helped to flatten the space between these Victorian houses—already decaying— and the rush of Hollywood advertising on the street. Just a few months earlier, in New Orleans, Evans had found a similar situation, photographing a two-story house with a ketchup ad for a neighbor. In the New Orleans image, the house is skittering with activity. Whole families lean out over balconies. The house is framed in its entirety and can be read like an advent calendar, with each columned bay revealing human activity. The billboard is cut off at the edge of the picture. In Atlanta, the houses are unpeopled, maybe uninhabited. The commercial hunger of Hollywood is outpacing the architecture.

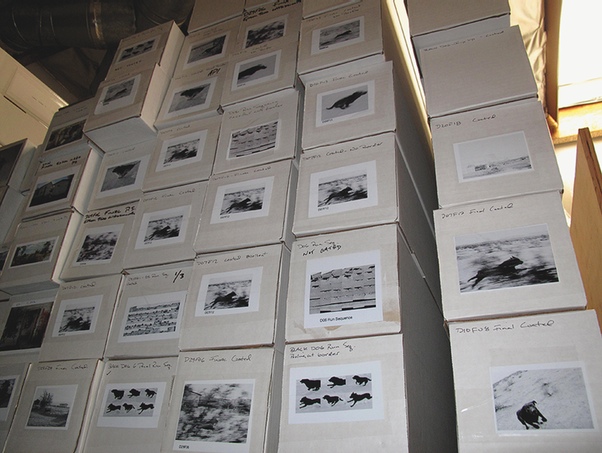

Despite this clash between the residential and the mercantile, Evans’s picture-making style is, as ever, formally direct and solid. Its straightforward geometry makes it easy to look at this image and imagine the movie posters lasting as long as Roman inscriptions. Three years later, however, John Vachon, having started at the FSA as a file clerk, was sent to the Deep South for the first time as a photographer. He immediately tried to locate the houses in Evans’s picture. “I found the very place, and it was like finding a first folio Shakespeare. The signs on the billboard had changed, but I photographed it, and it’s in the file.” The two pictures together are a Muybridge-ish study of the ways an American house is as much a unit of measure of the country’s commercial climate as it is a home.

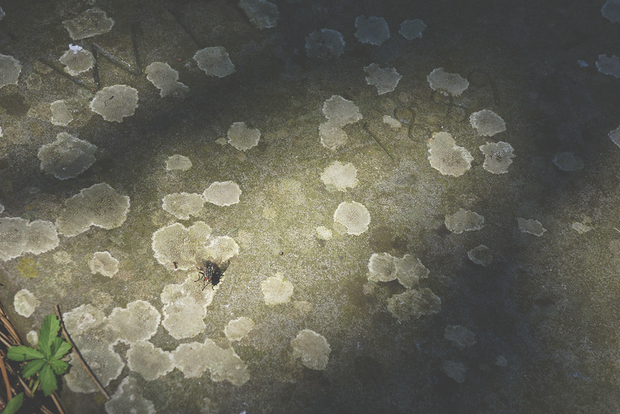

Evans was delighted with his finds. Restlessly modern, he saw progress in old houses giving way to new advertisements. As the twentieth century rolled along, these piquant, ironic incursions into domestic life gave way to heady despair at the spread of the housing-industrial complex. Robert Adams’s What We Bought (1970–74) plotted the spread of housing as a metastasizing growth in the Denver landscape. In its opening image, a big square creosote bush sits in middle of the frame in the middle of the prairie. It’s white hot and timeless, except for the creep of prefab development deep in the background. From there, houses spring up on and are dug into the land. At the edge of the city, they struggle for space—both in the world and in the frame—in a jungle of convenience stores and service (Gigantic Cleaners, Birdie’s Hair Styling). By plate 51, beyond the final ring road, the new houses reign supreme, and it’s a wasteland of a kingdom. Houses are packed into lots spread soullessly to the horizon. It’s always midday. The housing itself has become industrial. You can’t imagine the buildings being built: they feel extruded or minted or mined. The photographer is angry at this development, and his pictures have some of the sentiment of Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang: “These machine-made wastes grew up in tumbleweed and real-estate development, a squalid plague of future slums constructed of green two-by-fours, dry-wall fiberboard and prefab roofs that blew off in the first good wind.”

Photography is a complicated form of protest, though, because the camera is so accepting. Cameras are golden retrievers, and the world is a tennis ball. Adams is clearly horrified at the infectious spread of the prefab, but his photographs can’t help being moved by its patterns and symmetry and novelty. As photography moves to its new digs in the glitzy high rises of Contemporary Art, the seduction of American housing, even in its ticky-tacky suburban spread, tends to almost outstrip the politics and social concerns of its makers. The works in Todd Hido’s series Houses at Night are first-person accounts of life on the ground in this postpolitical neighborhood. The houses he photographs are exactly those Abbey described, barely able to survive their poor construction in the onslaught of car culture and the cul-de-sac. Hido’s pictures have a color palette all their own, an acidic roux of film emulsion and the color temperature of mercury- and sodium-vapor industrial lighting, in combinations no painter would stir up. And they are very much about this color, how photographic and how god-awful glamorous it is. Reasons and responsibilities, class and race and zoning and planning, fade into a sublime haze.

Larry Sultan’s series The Valley sums up the trajectory from house as social document to private fantasy beautifully. In Backyard, West Valley Studio, 2003, we have landed back in Carleton E. Watkins’s California. Again housing slips to the background of a vital U.S. industry. But this one is designed to bypass sight and cognition, and head straight for the pleasure centers. The housing on the other side of the fence, which could have been cropped easily from an Adams or a Hido, is a scrim, put up to protect a pornographic spectacle from real neighbors in real houses. Someday, on this spot, there will be a Superfund site and a museum.

Tim Davis is an artist and writer living in Tivoli, New York. His new project, an album of songs with accompanying music videos, is called It’s OK to Hate Yourself. He teaches photography at Bard College.

SUBSCRIBE TO TIM DAVIS’S MAILBOX OF THE MONTH CLUB and receive twelve signed, limited-edition monthly postcards of photographs of mailboxes sent to your mailbox.

Image credits:

Carelton E. Watkins, Hacienda, View East, 1863. Courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Walker Evans, Houses, Atlanta, Georgia, 1936. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection.

John Vachon, Houses, Atlanta, Georgia, 1938. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection.

Robert Adams, Untitled (Mobile Home Park), 1970–74. Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, 1998–2002. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

Todd Hido, #7373, 2009, from the series Houses at Night. Courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York.

Larry Sultan, Suburban Street in Studio, 2000. From the series The Valley. Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan.